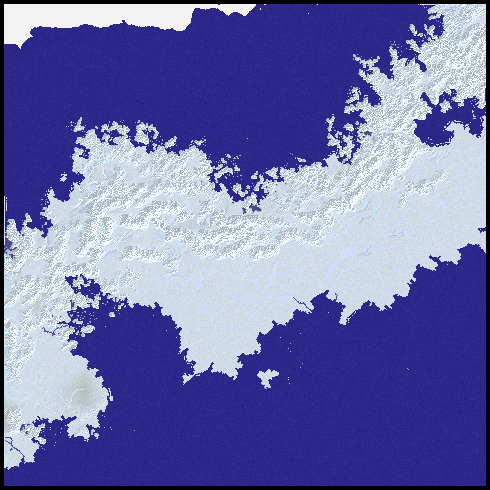

So first, here are some screenshots. These are all from a single sample world:

The major benefit is, once again, a tremendous speed increase. As I mentioned previously, the old version of Undiscovered Worlds could take about a minute to generate each map like these. The new version takes about four or five seconds for each one. This makes it far pleasanter to work on the code as well as actually browsing the worlds it creates. And for me at least, that alone makes it worth taking all the time to convert this all to C++.

Of course there are lots more changes along the way. I was able to find and eliminate quite a lot of bugs. Fortunately, I was also able to generate some new and even more baffling ones, just to keep things interesting. Here are some of the key developments:

Rivers

In the original version, rivers could carve out the land under them, potentially below sea level, creating estuaries and inlets. (They weren't really carving it out, because rivers are generated before the rest of the land, but that was the effect.) I found that this led to all sorts of bugs and problems and piled function upon function trying to resolve those problems, which were mostly associated with potentially allowing inlets to appear far inland where sea wasn't otherwise expected to be. Now rivers still carve in this way, but I don't allow them to drop below sea level. So rivers will not carve out inlets and estuaries. This resolves a lot of problems and makes some other things possible (see below).

But what about all those nice inlets? Well, they're easily dealt with. I just added a new function to add them. It looks for where rivers meet the sea and cuts out inlets based on their size. Although this is a more artificial way of doing it than letting the rivers make their own inlets (which is how Martin O'Leary does it, after all), I find it gives better results.

There are various other tweaks. I added extra wiggles to rivers that pass from one corner of a tile to the opposite one - these sections of rivers had tended to come out too straight in the previous version, but now they look a bit more natural. As always, the struggle at regional level is to prevent the map from looking like it's made up of square tiles, and this helps.

There are various other tweaks. I added extra wiggles to rivers that pass from one corner of a tile to the opposite one - these sections of rivers had tended to come out too straight in the previous version, but now they look a bit more natural. As always, the struggle at regional level is to prevent the map from looking like it's made up of square tiles, and this helps.

Coastlines

As I may have mentioned before, coastlines have caused me unending problems, and the new version is no exception. I managed to get coastlines in the old version looking pretty decent a fair amount of the time, so I was annoyed when transposing exactly the same routines to the new version delivered blocky, unconvincing coasts most of the time. I spent a lot of time trying all kinds of methods to rectify this. I eventually found a combination of methods helped:

- I found that particular heights of the land at coasts, combined with particular depths of seas there, tended to produce better results. (This is something that would have taken forever to work out with the slower, older version.) So I added a function at the end of the global terrain generation that goes through the coasts and pushes the heights/depths towards these optimum values.

- I had previously used blobby templates (in fact the same ones used for making small lakes) to break coastlines up a bit, using them to subtract land where the coasts were too straight. I added the ability to subtract land at these points too and I also allowed it to use larger templates, not just the very small ones I'd previously restricted it to. This made for really good results.

- I had previously created the effect of fjords in glacial regions by extending mountain ranges out beyond the coasts. When I did this, I also set UW to extend occasional mountain ranges out in the same way in other locations, just to get occasional peninsulas. I greatly extended this in the new version. Peninsulas of this kind are much more common, especially in areas of greater general roughness, and they can occur even when only small hills are near the coasts. This makes for areas of coastline that are fairly jagged (though not to the extend of the fjord coasts, where more mountains are extended out and for longer). It also often creates islands off the tips of peninsulas, which look rather good. I found this method so effective at creating interesting coastlines that it was hard to find a balance between using it enough to make a difference and using it too much so that all coastlines look the same. I really want variety in the maps, but it's not easy to achieve.

So all of this helped to make the coastlines look pretty decent most of the time - although as before there are always a few bits that look annoying blocky or boring or whatever.

I was also able to make other changes, particularly with regard to "pools", or sections of sea that are cut off from the rest of the sea, which are unavoidable when generating coastlines in this way but which are obviously highly unrealistic. Previously, I used a flood fill function to find and eliminate these, but it was clunky and didn't always work. Now, though, having removed the ability of rivers to cut below sea level, I could guarantee that sea would never appear more than one tile away from the coast. This allowed me to create a new approach to pools: a simple pathfinding function. The program identifies which tiles are roughly on the coast (either tiles that correspond to land cells on the world map that border sea cells, or sea cells that border land ones). It goes through these tiles on the regional map, finding any sea cells they contain. It then identifies sea cells in neighbouring tiles that are further out to sea, and tries to trace a path to them. If it can't find such a path, it declares the start cell to be part of a pool and turns it into land.

Excursus on my pathfinding algorithm. Ignore this if you're one of those weird people who are inexplicably uninterested in pathfinding algorithms.

I didn't use A* or any other standard pathfinding algorithm for this. Instead I wrote a simple recursive function to do it. Now standard pathfinding algorithms are breadth-first: that is, they start from the start cell, then look at each of the neighbouring cells in turn, then look at each of their neighbouring cells in turn, and so on. A recursive function like mine doesn't do that. It's a depth-first algorithm: it looks in one direction first and exhausts all possibilities in that direction before turning to the next. This is usually fairly inefficient. However, a little improvement occurred to me which I haven't found in any of the sites on pathfinding algorithms that I looked at - though someone must have done it before because it's both fairly obvious and surprisingly effective.

The function works by moving to the north and calling itself, then moving to the east and calling itself, then to the south and calling itself, then to the west and calling itself. Then it returns, either to the previous recursion of itself, or the original calling function. That's a very basic recursive method.

But (this is my innovation), each time the function is called, before it calls itself again it checks to see what direction the target cell is in from the current location. It then changes the order of the directions based on that. For example, if the target cell is roughly south-southwest, it will move south and call itself, then move west and call itself, then move east and call itself, then move north and call itself. The order of the recursive calls is based on how likely it is that that direction will actually lead to the target.

This means that if there are no barriers in the way, the pathfinding function will simply go straight to the target cell without deviating at all. That's obviously quicker and more efficient even than A*.

However, there are two disadvantages. The first is that, as a recursive function, it risks a stack overflow if it calls itself too many times. That means it can't search over large areas without crashing.

However, there are two disadvantages. The first is that, as a recursive function, it risks a stack overflow if it calls itself too many times. That means it can't search over large areas without crashing.

The second is that if there are barriers in the way from the start to the target, it won't be very efficient. It will be like a fly bumping at a window trying to bash through it. Unlike the fly, it will find its way around eventually, but the path it comes up with will not be the optimal one and it will take longer than a more sophisticated breadth-first algorithm.

But I reasoned that neither of these was a big problem. First, if I was only trying to find a path from one tile to its neighbouring one, these are small areas that won't cause a crash. Second, most of the time, there would be a direct path from the start to the target, or one without too many obstacles, so my function would probably be pretty efficient for its purpose. And third, I don't care about getting a good path. I don't care what the path is, only whether there is one at all.

Gratifyingly, all of this proved correct. The pathfinding technique works well and very quickly.

End of boring excursus

A problem with this, though, is that it couldn't account for the extended mountain ranges, which stick out into the sea in fjord regions and elsewhere. These can create pools that are further from the coast than normal ones. My pathfinding routine couldn't cope with those. Eventually I solved this by creating a new flood-fill routine that goes over the map after the other ones. Like the one in the original version of UW, it looks for areas of sea that are smaller than a certain area. Instead of turning them into land, though, it turns them into lakes. The result of this is that crinkly coastlines tend to have crinkly-shaped lakes a little way inland, which I think looks rather good.

Deltas

Deltas can now be bigger and have more branches. However, this created a new problem. Delta branches are a river system of their own, which ignore other rivers, except for where they connect up with their host river. Any other rivers that may wander across the delta region don't interact with them. I originally thought this would help to create the impression of a confused watery area, but it actually detracts from the nice fan shape of the delta to see other rivers just going straight across it. So I created a function at the global river generation stage which diverts rivers of this kind. Now, if a river enters the delta of another river, it will change direction to follow one of the branches of that delta down to the sea. Because the routes of delta branches across tiles are calculated independently of the routes of normal rivers across the same tiles, this means that the two will cross, merge, and separate as they meander together through the same tiles on their way to the sea, which I think is quite a nice effect. It was a nightmare getting this relatively simple-sounding tweak to actually work, though.

Terrain roughness

Most of the terrain is created by taking height values from the global map and then filling in the tiles around them using the diamond-square algorithm. That algorithm uses a roughness value to determine how much variation to give the land: if that value is low, it simply graduates smoothly from one initial value to the next; if it is high, it crinkles up and down wildly as it goes. In the previous version, this roughness value varied slightly from tile to tile depending on the global roughness value. But it couldn't vary much, because then the boundaries between tiles were too apparent, where the land abruptly changed from being rough to smooth. Now, though, it occurred to me that the roughness value itself could be smoothed with the diamond-square algorithm. That is, the regional map itself now has an array storing its own roughness values. These are seeded from the global roughness values for each tile and then the rest are extrapolated via diamond-square, exactly as precipitation and temperature are already done. Now, when the program creates the terrain, it changes the roughness value within each tile as it does them. That means that within a single tile you can have areas with high roughness and others with low. This allows us to change the roughness gradually, not just at tile boundaries. And that allows us to have areas with relatively high roughness, rather than having everywhere be pretty flat apart from the mountain ranges, as in the old version. This adds more variety and texture to the maps, I think.

Lakes

They're evil and I hate them. Something went wrong with my lake coastline routines and they generated terrible results. I squodged together so many new ones to try to repair them that I don't really understand how they work any more, but they roughly work, though the lake shorelines tend to look implausibly crinkly. Only when I was taking the screenshots for this very post did I discover that lakes now have a tendency to crash the program. Why is that? Who knows! It'll have to be investigated. At any rate, they exist and they mostly don't appear to breach the laws of physics, and that's the best anyone can hope for with lakes.

I haven't yet implemented rift lakes at the regional level, because I'm not really happy with the old implementation and I want to try doing them in a different way, so I thought I'd save that for another blog post.

Where next?

Well, I asked this before, and my answer was to rewrite the whole thing rather than move on to something new. Now I've done that. What now? Well, as will be apparent from the above, there are lots of bugs to squash and remaining features to add in. Features that it needs next include:

Well, I asked this before, and my answer was to rewrite the whole thing rather than move on to something new. Now I've done that. What now? Well, as will be apparent from the above, there are lots of bugs to squash and remaining features to add in. Features that it needs next include:

- The ability to scroll around the map more quickly. At the moment it generates the entire regional map every time you scroll, even by one tile. Obviously it's more efficient only to generate the new bit. I've deliberately not done this yet because I wanted to be sure that everything was working consistently and that each tile looked the same no matter where in the regional map it appeared.

- The ability to generate regional maps of larger areas, not just the 30x30 square that it does by default. I think this would be really nice.

- Possibly a new scale with larger worlds. If I were to double the height and width of the global map, it would have four times as much detail. That would mean that on the regional maps, one cell would be 1km square rather than 2km square. I wouldn't change how they are actually generated as I think that this scale would actually fit the features I have on them now.

Once I've done that, I'll aim to release something that other people can use and find appalling bugs in too. Yay!

That sounds pretty close to A*, honestly. The whole point of A* is to have a heuristic that guides decision-making based on how likely each new step is to lead to a path. I use a variant I call A**, which is just A* with multiple possible end-points. Takes forever, though, since I'm using the height between cells as the pathfinding weight. Glad to hear your method works!

ReplyDeleteYes indeed, A* is a breadth-first search with a guiding heuristic. Mine is a depth-first search with a guiding heuristic. B*, maybe?

Delete